In a piece of music, every note corresponds to a specific pitch on the instrument for which the piece was written. For example, every note in a piece of written piano music corresponds to a specific key on a piano keyboard. To read and play the proper pitches that the notes in a piece of music represent, you need to know:

- How notes are named

- How clefs work

- How key signatures work

How Notes are Named

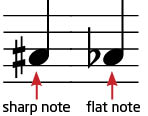

Notes are named using the first seven letters of the alphabet—A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. These notes are called naturals. Notes that occur between the naturals are called sharps and flats.

A note followed by a sharp symbol (#) indicates a note with a higher pitch than the natural—for example, F# occurs between F and G. A note preceded by a flat symbol (b) indicates a note with a pitch lower than the natural—for example, Bb falls between A and B. A note with the same sound can be named either as a sharp or its equivalent flat. In the following illustration of an octave, the note that comes between D and E can be written either as D# or Eb. All the notes, including sharps and their flat equivalents in parentheses, are:

A – A# (Bb) – B – C – C# (Db) – D – D# (Eb) – E – F – F# (Gb) – G – G# (Ab)

Octaves

Many notes share the same letter name but differ in pitch—some sound low and deep, while others sound high and clear. In this illustration of a piano, there are two A-notes an octave apart. The term octave comes from the Latin word for “eight” and represents the eight-note span between two notes with the same name. The complete set of notes (naturals, sharps, and flats) in that span is referred to as being “in the same octave.”

Clefs

A clef is a symbol placed at the beginning of the staff that tells a musician which notes correspond to the lines and spaces of the staff. Of the many clefs in Western music, the most common are the treble clef (for high notes) and the bass clef (for low notes). The treble clef assigns the following notes to the five lines of the staff: E (first line), G, B, D, F (fifth line). Simply by changing the clef, a composer can instantly switch the note that each line and space on the staff represents.

Why Use Clefs?

Intuitively, it might seem that it would be easier to read music if the lines and spaces of the staff always corresponded to the same set of notes. But clefs actually make it easier to read and play music, since they allow composers to shift the location of notes on the staff to best accommodate the range of pitches that a given instrument typically plays. As a result, music can be written using fewer ledger lines, which makes it easier to read.

Key Signatures

The key signature of a piece of music indicates the key of the piece of music, which dictates which notes in the piece should be played as sharps or flats. For more on sharps, flats, keys, and key signatures, see How to Read Key Signatures.

How Note Names, Clefs, and Key Signatures Work Together

When you look at a piece of music for the first time, you’ll need to understand the clef and key signature.

- Reading the clef: Typically, all music for a given instrument is written in the same clef, so you’ll likely only need to learn the notes and their corresponding pitches for your instrument’s clef (or clefs). For instance, violinists and guitarists almost always read treble clef, whereas piano players always read bass and treble clefs together (a notation called the grand staff).

- Reading the key signature: You need to read the key signature of every piece you play to know which notes to play as sharps, flats, or naturals.

The clef and key signature tell you only which pitches to play—it’s up to you to know where and how to play those pitches on your instrument. For example, once you learn to read the clef and key signature to determine that a note on the first line of the treble staff is an E, you need to know where that E occurs on your instrument and how to play it.